I hear a common set of questions from beginning programmers who feel they are struggling to get started.

I hear a common set of questions from beginning programmers who feel they are struggling to get started.

- Why is programming so hard?

- How long does it take to be a good programmer?

- Should I consider a different career?

It is difficult to give a general answer to these questions, because the answers depend on the characteristics of the questioner.

I was fortunate to be a beginner when I was 13 years old. My parents saw a Texas Instruments 99/4A computer on sale at a department store and, on a whim, made a purchase. I find it ironic that department stores don’t sell computers anymore, but you can use a computer to buy anything you can find at a department store (as well as the junk bonds issued by those stores).

Despite all the improvements in the hardware, software, languages, and tools, I think it is harder to get started today than it was in the early days of the personal computer. Here are three reasons:

1. Applications today are more ambitious. ASCII interfaces are now user experiences, and even the simplest modern app is a distributed system that requires cryptography and a threat model.

2. Expectations are higher. Business users and consumers both expect more from software. Software has to be fast, easy, available, and secure.

3. Information is shallow.There’s plenty of content for beginners, but most of the material doesn’t teach anything with long term value. The 9 minute videos that are fashionable today demonstrate mechanical steps to reach a simplistic goal.

In other words, there is more to programming these days than just laying down code, and the breadth of knowledge you need keeps growing. In addition to networking, security, and design, add in the human elements of communication and team work. This is similar to the point in time when, to be a good physicist, you only needed to grasp algebra and geometry.

My suggestions to new developers are always:

1. Write more code. The more code you write, the more experience you’ll gain, and the more you’ll understand how software works. Write an application that you would use every day, or try to implement your own database or web server. The goal isn’t to build a production quality database. The goal is to gain some insight about how a database could work internally.

2. Read more code. When I started programming I read every bit of code I could find, which wasn’t much at the time. I remember typing in code listing from magazines. These days you can go to GitHub and read the code for database engines, compilers, web frameworks, operating systems, and more.

3. Have patience. This does take time.

As for the career question, I can’t give a yes or no answer. I will say if code is something you think about when you are not in front of a computer, than I recommend you stick with programming, you’ll go far.

From the outside, most software development projects look like a product of intelligent design. I think this is the fault of marketing, which describes software like this:

“Start using the globally scalable FooBar service today! We publish and consume any data using advanced machine learning algorithms to geo-locate your files and optimize them into cloud-native bundles of progressive web assembly!”.

In reality, developing software is more like the process of natural selection. Here’s a different description of the FooBar service from a member of the development team:

“Our VP has a sister-in-law who is a CIO at Amaze Bank. She gave our company a contract to re-write the bank’s clearinghouse business, which relied on 1 FTP server and 25 fax machines. Once we had the basic system in place the sales department started selling the software to other banks around the world. We had to localize into 15 different languages and add certificate validation overnight. Then the CTO told us to port all the code to Python because the future of our business will be containerized micro machine learning services in the cloud”.

This example might be a little silly, but software is more than business requirements and white board drawings. There are personalities, superstitions, random business events, and, tradeoffs made for survival.

In my efforts as a trainer and presenter I’ve been, at times, discouraged from covering the history of specific technical subjects. “No one wants to know what the language was like 5 years ago, they just want to do their job today”, would be the type of feedback I’d hear. I think this is an unfortunate attitude for both the teacher and the student. Yes, history can be tricky to cover. Too often the history lesson is an excuse to talk about oneself, or full of inside jokes. But, when done well, history can be part of a story that transforms a flat technical topic into a character with some depth.

As an example, take the April 2017 issue of MSDN Magazine with the article by Taylor Brown: “Containers – Bringing Docker To Windows Developers with Windows Server Containers”. Throughout the article, Brown wove in a behind the scenes view of the decisions and challenges faced by the team. By the end, I had a better appreciation of not only how Windows containers work, but why they work they way they do.

For most of the general population, making software is like making sausages. They don’t want to see how the sausage was made. But, for those of us who are the sausage makers, a little bit of insight intro the struggles of others can be both educational and inspirational.

My latest course on Pluralsight cover a range of topics centered around building secure services.

The first topic is software containers. I’ll show you how to work with Docker tools to run .NET Core software in Windows and Linux containers, and how to deploy containers into Azure App Services.

We’ll also look at automating Azure using Resource Manager templates. Automation is crucial for repeatable, secure deployments. In this section we’ll also see how to work with Azure Key Vault as a place to store cryptographic keys and secrets.

The third module focuses on Service Fabric. We’ll see how to write stateful and stateless services, including an ASP.NET Core Web application, and host those services in a service fabric cluster.

Finally, we’ll use Azure Active Directory with protocols like OIDC and OAuth 2 to secure both web applications and web APIs. We’ll also make secure calls to an API by obtaining a token from Azure AD and passing the token to the secure API, and look at using Azure AD B2C as a replacement for ASP.NET Identity and membership.

With this course I now have over 14 hours of Azure videos available. You can see the entire list here: https://www.pluralsight.com/authors/scott-allen

When a system needs more resources, we should favor horizontal scale versus vertical scale. In this document, we’ll look at scaling with some Microsoft Azure specifics.

When we scale a system, we add more compute, storage, or networking resources to a system so the system can handle more load. For a web application with customer growth, we’ll hopefully reach a point where the number of HTTP requests overwhelm the system. The number of requests will cause delays and errors for our customers. For systems running in Azure App Services, we can scale up, or we can scale out.

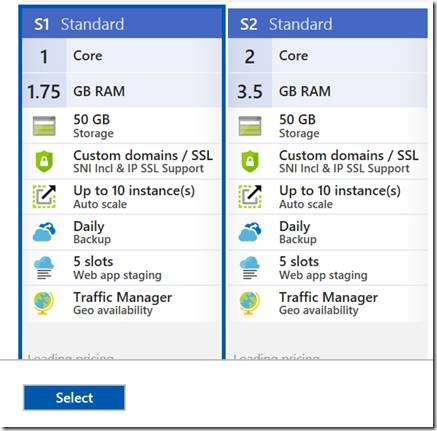

Scaling up is replacing instances of our existing virtual hardware with more powerful hardware. With the click of a button in the portal, or a simple script, we can move from a machine with 1 CPU and 1.75 GB of memory to a machine with double the number of cores and memory, or more.

We sometimes refer to scaling up (and down) as vertical scaling.

Scaling out is adding more instances of your existing virtual hardware. Instead of running 2 instances of an App Service plan, you can run 4, or 10. The maximum number depends on the pricing tier you select.

Scaling out and in is what we call horizontal scaling.

Horizontal scaling is the preferred scale technique for several reasons.

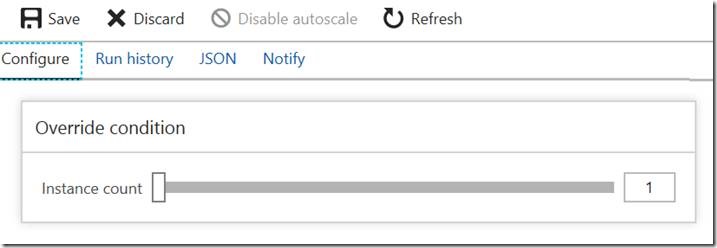

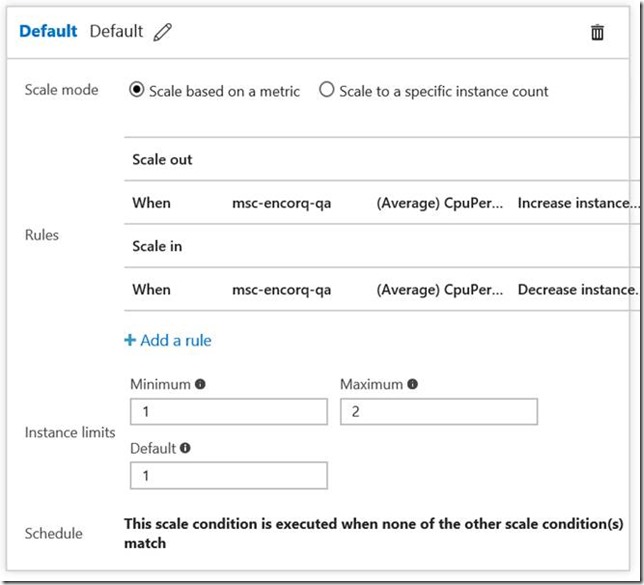

First, you can program Azure with rules to automatically scale out. Likewise, you can also apply rules to scale in when the load is light.

Secondly, horizontal scale adds more redundancy to a system. Commodity hardware in the cloud can fail. When there is a failure, the load balancer in front of an app service plan can send traffic to other available instances until a replacement instance comes on-line. We want to test a system using at least two instances from the start to ensure a system can scale in the horizontal direction without running into problems, like when using in-memory session state. Make sure to turn off Application Request Routing (ARR) in the app service to make effective use of multiple instances. ARR is on by default, meaning the load balancer in front of the app service will inject cookies to make a user’s browser session sticky to a specific instance.

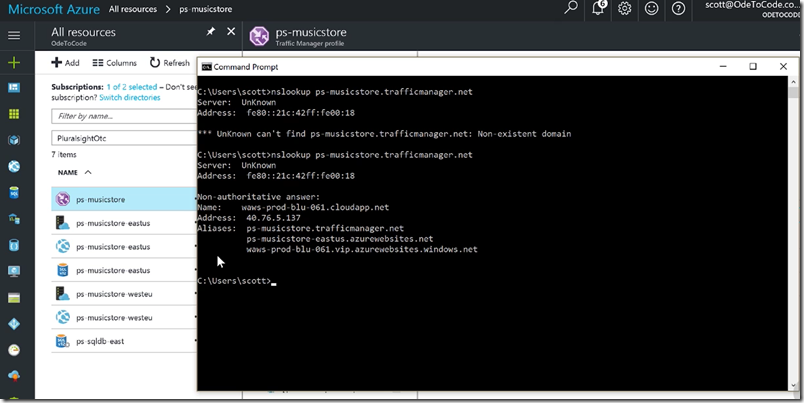

Thirdly, compared to vertical scaling, horizontal scale offers more headroom. A scale up strategy can only last until we reach the largest machine size, at which point the only choice is to scale out. Although the maximum number of instances in an App Service plan is limited, using a DNS load balancer like Azure Traffic manager allows a system to process requests across multiple app service plans, and the plans can live in different data centers, providing additional availability in the face of disaster and practically an infinite horizontal scale.

There are some types of systems which will benefit more from a scale up approach. A CPU bound system using multiple threads to execute heavy processing algorithms might benefit from having more cores available on every machine. A memory bound system to manipulate large data structures might benefit from having more memory available on every machine.

The only way to know the best approach for a specific system is to run tests and record benchmarks and metrics.

Scale up and scale out are two strategies to consider for scaling specific components of a system. Generally, we consider these two strategies for stateless front-end web servers. Other areas of a system might require different strategies, particularly networking and data storage components. These components often require a partitioning strategy.

Partitioning comes into play when an aspect of the system outgrows the defined physical limits of a resource. For example, an Azure Service Bus namespace has defined limits on the number of concurrent connections. Azure Storage has defined limits for IOPS on an account. Azure SQL databases, servers, and pools have defined limits on the number of concurrent logins and database transaction limits.

To understand how partitioning works, and the nuances of choosing a partitioning strategy, consider the following scenario.

You own a transportation company. You have a contract to transport a party of 75 people from downtown to the airport at exactly 9:30 in the morning. You own a fleet of buses, but each bus only holds 50 people. Everyone must leave at the same time, and you must let every person know which bus they will ride on before they arrive.

The above scenario is an example of a situation that requires partitioning. Since there is no vehicle with a capacity of 75, you’ll need to partition the 75 individuals across 2 vehicles. That’s the easy part to see. The harder part is coming up with a partitioning strategy so you’ll know where everyone will go, and where to find them later. You could partition by the first letter of last name (A-M on one bus, N-Z on another), or age range, or gender. We must understand our data to choose an effective, scalable partitioning strategy for our data.

Likewise, if you need more concurrent connections than a single Service Bus endpoint can provide, you’ll need to add more endpoints and partition your tenants, customers, and client applications across the endpoints.

Many database systems refer to partitioning as sharding, and in databases systems there are often additional concerns to consider when selecting a partitioning strategy. ACID transactions may be impossible, or at least incredibly expensive, to enforce across partitions. Thus, you also need to consider the behavior and consistency requirements of a system when considering a partitioning strategy. For SaaS, the tenant ID is often part of the partitioning strategy.

There is no single best solution for scale. We need to amalgamate our business requirements and cost factors with an understanding of our data and an understanding of how our system behaves at run time to determine the best strategy for scale. Here are some steps that will help.

1. Understand your business requirements, specifically when it comes to cost per tenant and the desired availability levels. Will you have a service level agreement with your customers? Cost factors and SLAs influence the amount of availability to build into the system. Availability influences the amount of redundancy to build into a system, and redundancy will influence cost and can influence scalability since more resources are in play.

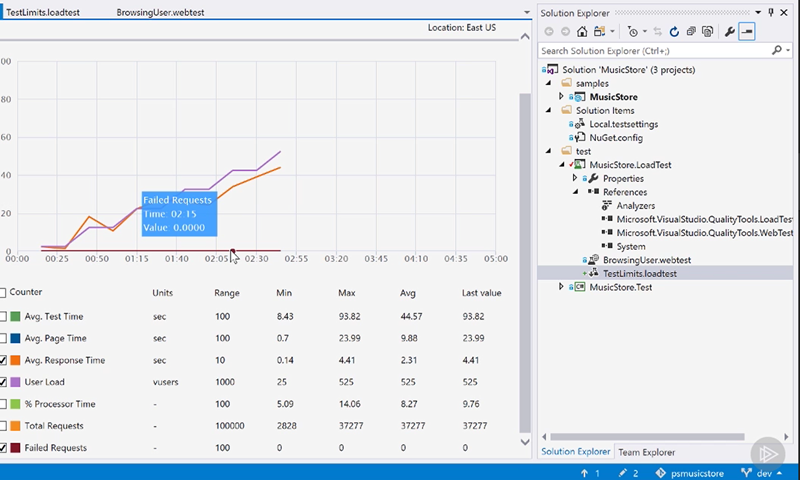

2. Understand how the system behaves under load before the load arrives. Also, understanding how the system responds to different scale strategies. Load testing is vital to understanding both of these aspects of the system. You need to know the baseline behavior of the system under a normal load, and where the system fails when the load increases. How will your system behave if give it more headroom on a single machine versus more instances of the same machine? Although replicating real user behavior in a load test is difficult, knowing approximate answers to these questions will help you devise a cost effective strategy to scale.

Do you want to design a resilient, scalable system in the cloud? Have you wondered what platforms and services Microsoft Azure offers to make building resilient, scalable systems easier?

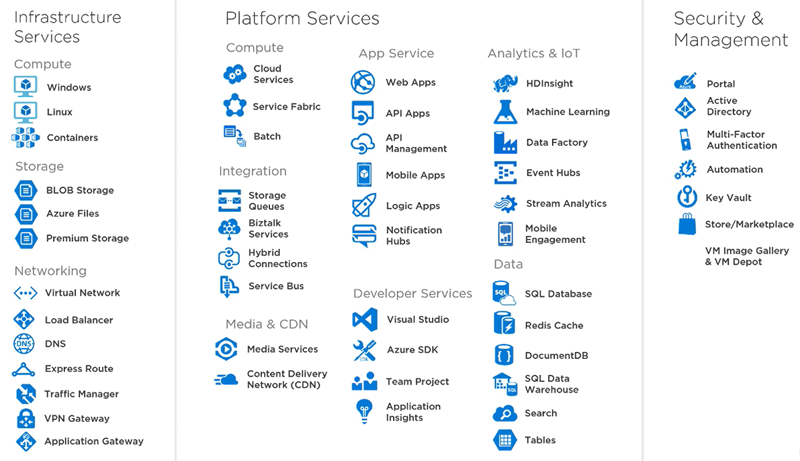

Last month I released a new course on design patterns for the cloud with a focus on Microsoft Azure. The first of the four modules in this course provides an overview of the various platforms and services available in Azure, and also demonstrates a few different system designs to show how the various resources can work together.

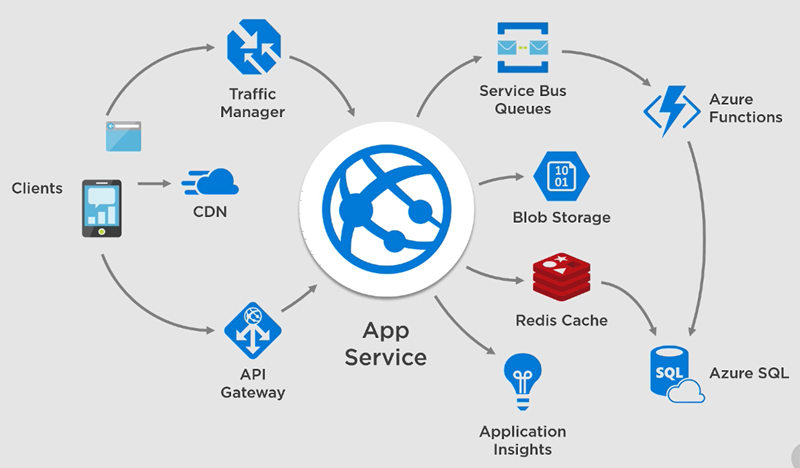

The second module of the course is all about building resilient systems – systems that are highly available and recover from disasters small and large. You’ll see how to use resources like Azure Service Bus and Azure Traffic Manager.

The third module is all about scalability. We will talk about partitioning, sharding, caching, and CDNs. We’ll also take a look at the Azure API Management service and see how to build an API gateway.

The last module demonstrates how to use the load testing tools in Visual Studio and VSTS Online. It’s important to stress your systems and prove their scalability and resiliency features.

I’m pleased with the depth and breadth of the technical content in this course. I hope you enjoy watching it!

For the last 10 months I’ve been working with Azure Functions and mulling over the implications of computing without servers.

If Azure Functions were an entrée, I’d say the dish layers executable code over unspecified hardware in the cloud with a sprinkling of input and output bindings on top. However, Azure Functions are not an entrée, so it might be better to describe the capabilities without using culinary terms.

With Azure Functions, I can write a function definition in a variety of languages – C#, F#, JavaScript, Bash, Powershell, and more. There is no distinction between compiled languages, interpreted languages, and languages typically associated with a terminal window. I can then declaratively describe an input to my function. An input might be a timer (I want the function to execute every 2 hours), or an HTTP message (I want the function invoked when an HTTPS request arrives at functions-test.azurewebsites.net/api/foo), or when a new blob appears in a storage container, or a new message appears in a queue. There are other inputs, as well as output bindings to send results to various destinations. By using a hosting plan known as a consumption plan, I can tell Azure to execute my function with whatever resources are necessary to meet the demand on my function. It’s like saying “here is my code, don’t let me down”.

Azure Functions are cheap. While most cloud services will send a monthly invoice based on how many resources you’ve provisioned, Azure Functions only bill you for the resources you actively consume. Cost is based on execution time and memory usage for each function invocation.

Azure Functions are simple for simple scenarios. If you have the need for a single webhook to take some data from an HTTP POST and place the data into a database, then with functions there is no need to create an entire project, or provision an app service plan.

The amount of code you write in a function will probably be less than writing the same behavior outside of Azure Functions. There’s less code because the declarative input and output bindings can remove boilerplate code. For example, when using Azure storage, there is no need to write code to connect to an account and find a container. The function runtime will wire up the everything the function needs and pass more actionable objects as function parameters. The following is an example function.json file that defines the bindings for a function.

{

"disabled": false,

"bindings": [

{

"authLevel": "function",

"name": "req",

"type": "httpTrigger",

"direction": "in"

},

{

"name": "$return",

"type": "http",

"direction": "out"

}

]

}

Azure Function are scalable. Of course, many resources in Azure are scalable, but other resources require configuration and care to behave well under load.

One criticism of Azure functions, and PaaS solutions in general, is vendor lock-in. The languages and the runtimes for Azure Functions are not specialized, meaning the C# and .NET or JavaScript and NodeJS code you write will move to other environments. However, the execution environment for Azure Functions is specialized. The input and output bindings that remove the boilerplate code necessary for connecting to other resources is a feature only the function environment provides. Thus, it requires some work to move Azure Function code to another environment.

One of the biggest drawbacks to Azure functions, actually, is that deploying, authoring, testing, and executing a function has been difficult in any environment outside of Azure and the Azure portal, although this situation is improving (see The Future section below). There have been a few attempts at creating Visual Studio project templates and command line tools which have never progressed beyond a preview version. The experience for maintaining multiple functions in a larger scale project has been frustrating. One of the selling points of Azure Functions is how the technology is so simple to use, but you can cross a threshold where Azure Functions become too simple to use.

There have been a few announcements this year that have Azure Functions moving in the right direction. First, there is now an installer for the Azure Functions runtime. With the installer, you can setup an execution environment on a Windows server outside of Azure.

Secondly, in addition to script files, Azure Functions now supports a class library deployment. Class libraries are more familiar to most .NET developers compared to C# script files. Plus, class libraries are easier to author with Intellisense and Visual Studio, as well as being easier to build and unit test.

Azure Functions are hitting two sweet spots by providing a simple approach to put code in the cloud with the scripting model, while class libraries support projects with larger ambitions.

However, the ultimate goal for many people coming to Azure Functions is the cost effectiveness and scalability of serverless computing. The serverless model is so appealing, I can imagine a future where instead of moving code into a serverless platform, more serverless platforms will appear and come to your code.

Adding Feedback from Solvingj:

Great summary! I always look forward to your point of view on new .NET technologies.

I wanted to add some recent updates you will surely want to be aware of and perhaps mention:

-Deployment slots (preview)

-Built-In Swagger Support (getting there)

-The option to use more traditional annotation-based mapping of API routes

-Durable functions in beta

This enables a stateful orchestrator pattern, which is always on, can call other functions, etc. Whereas Azure Functions originally represented a paradigm shift away from monolithic ASP.NET applications with many methods to tiny stateless applications, durable functions represent a slight paradigm shift back the other way. I think the end-result is Azure Functions supporting a much broader (yet still healthy) range of workloads that can be moved over from ASP.NET monoliths, while maintaining it's "serverless" advantages.

-Continuous Integration

I know you're aware of this feature since it's been part of Azure App service for ages. However, you did not mention it, and for us, this was perhaps the most attractive feature. The combination of Azure Functions Runtime + GIT integration enables the complete elimination of whole categories of tedious DevOps engineering concerns during rapid prototyping. No Docker, no Appveyor, just GIT and an Azure Function App. Of course, you can still add Appveyor for automated testing when it makes sense, but it's not required early on.

Other Experiences

-Precompiled Functions

I happen to agree with Chris regarding precompiled functions. In fact, once we refactored away from the .csx scripts and into libraries, what we were left with was a normal ASP.net structure, with one project for the function.json files and all the advantages of the Azure Functions runtime (most mentioned here). Once we switched to using Functions with this pattern, the entire Cons section you described no longer applied to us.

-Bindings

One of the Cons we found that you did not mention was in the binding and configurations strategy. We liked the idea of declarative configurations and removal of boiler plate code for building external connections in theory. However, in practice, the output bindings were simply too inflexible for our applications. Our functions were more interactive, needing to make multiple connections to the outside within a single function, and the bindings did not provide our code a handle to it's connection managers. Thus, we ended up having to build our own anyway, rendering the built-in output bindings pointless. I submitted feature requests for this however.

Catching up on announcements …

About 3 months ago, Pluralsight released my Developing with Node.js on Microsoft Azure course. Recorded on macOS and taking the perspective of a Node developer, this course shows how to use Azure App Services to host a NodeJS application, as well as how to manage, monitor, debug, and scale the application. I also show how to use Cosmos DB, which is the NoSQL DB formerly known as Document DB, by taking advantage of the Mongo DB APIs.

Other topics include how to use Azure SQL, CLI tools, blob storage, and some cognitive services are thrown into the mix, too. An entire module is dedicated to serverless computing with Azure functions (implemented in JavaScript, of course).

In the finale of the course I show you how to setup a continuous delivery pipeline using Visual Studio Team Services to build, package, and deploy a Node app into Azure.

I hope you enjoy the course.

OdeToCode by K. Scott Allen

OdeToCode by K. Scott Allen