If you want to teach someone the very basics of computer programming, then JavaScript might be a good place to start.

- The syntax is flexible and uses only a handful of keywords, plus functions and objects.

- The language includes standard control flow structures (if/else, while, do, switch, throw).

- A beginning programmer would also have an easier time understanding a number of other popular languages, including Java, C#, and C++.

- JavaScript runtimes are ubiquitous.

- Knowing how to program in JavaScript is marketable skill.

Once you've settled on JavaScript as a starting language, then the next question is what tools and environment to use. Node.js might be a good place to start.

- Node is free and easy to install on all the popular desktop operating systems.

- As a pure JavaScript execution engine, you can start by explaining Javascript without explaining HTML DOM APIs.

- Node has a REPL for interactive programming

- Node has a large universe of packages to build anything from a web server to desktop applications.

- Node projects follow simple file system conventions.

- You can still pick any editor or IDE to work with the JavaScript language.

Using node and JavaScript to learn programming fundamentals is something I'm putting together for a future Pluralsight video, and it's working quite well.

GridFS is a specification for storing large files in MongoDB. GridFS will chunk a file into documents, and the official C# driver supports GridFS.

The following class wraps some of the driver classes (MongoDatabase and MongoGridFS):

public class MongoGridFs

{

private readonly MongoDatabase _db;

private readonly MongoGridFS _gridFs;

public MongoGridFs(MongoDatabase db)

{

_db = db;

_gridFs = _db.GridFS;

}

public ObjectId AddFile(Stream fileStream, string fileName)

{

var fileInfo = _gridFs.Upload(fileStream, fileName);

return (ObjectId)fileInfo.Id;

}

public Stream GetFile(ObjectId id)

{

var file = _gridFs.FindOneById(id);

return file.OpenRead();

}

}

The following code uses the above class to put a file into MongoDB, then read it back out.

var fileName = "clip_image071.jpg";

var client = new MongoClient();

var server = client.GetServer();

var database = server.GetDatabase("testdb");

var gridFs = new MongoGridFs(database);

var id = ObjectId.Empty;

using(var file = File.OpenRead(fileName))

{

id = gridFs.AddFile(file, fileName);

}

using(var file = gridFs.GetFile(id))

{

var buffer = new byte[file.Length];

// note - you'll probably want to read in

// small blocks or stream to avoid

// allocating large byte arrays like this

file.Read(buffer, 0, (int)file.Length);

}

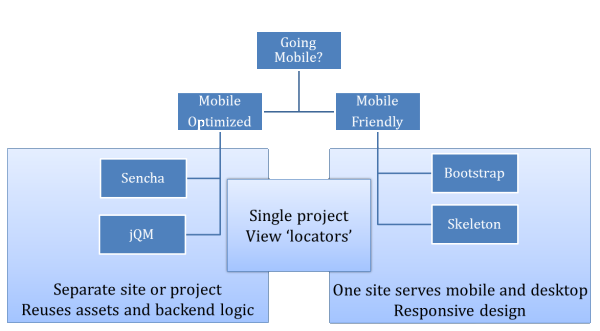

Assuming I already have an existing web site or web application deployed, running, and working great for desktop browsers, my decision tree for getting the site working on mobile devices looks something like the following.

The right-hand side, the "mobile friendly" approach, is primarily concerned with adding responsive design touches to an existing site. Frameworks like Bootstrap and Skeleton can make this easier, if they can be worked into the existing design. The right-hand side seems to work best with content heavy web sites (news, blogs, articles, and dashboards) with little interactivity from the user.

The left-hand side uses frameworks like jQuery Mobile to create the illusion of a native app. These frameworks generally require some major structural changes to the presentation layer and thus often work better as a separate site and source control project (m.server.com for mobile devices, server.com for the desktop, for example). A clean separation allows for a complete focus on the mobile experience, but there is still the possibility of reusing assets, media, and backend services previously built for the desktop version.

The middle box is a hybrid approach using a framework like ASP.NET MVC that allows for view selection at runtime (Index.cshtml and Index.mobile.cshtml). Although this approach makes it easy to reuse quite a bit of code (even into the UI layer of the server), and often takes less time, it sometimes sacrifices the optimizations that can be made when working from a clean slate and doesn't evolve as easily when adding new features. This approach might use just a CSS framework, or might use a framework like jQuery Mobile, while still keeping the ability to make structural changes like an entirely new site.

Like everything else in software, the decisions are all about tradeoffs and where the software has to go in the future.

Message handlers in the WebAPI feature a single method to process an HTTP request and turn the request into a response. SendAsync is the method name, and following the TAP, the method returns a Task<HttpResponseMessage>.

There are several different techniques available to return the Task result from a message handler. The samples on the ASP.NET site demonstrate a few of these techniques, although there is one new trick for .NET 4.5.

What you'll notice in these samples is that there is never a need to call Task.Run, or Task.Factory.StartNew, or use a Task constructor.

First, some message handlers will only need to process or modify the incoming request and not touch the response. In these cases the code can just return the result of the base SendAsync method (from DelegatingHandler). A good example is the MethodOverrideHandler sample on the ASP.NET site, which uses the presence of a header to change the HTTP method and thereby support clients or environments where HTTP PUT and DELETE messages are otherwise impossible.

public class MethodOverrideHandler : DelegatingHandler

{

readonly string[] _methods = { "DELETE", "HEAD", "PUT" };

const string _header = "X-HTTP-Method-Override";

protected override Task<HttpResponseMessage> SendAsync(

HttpRequestMessage request, CancellationToken cancellationToken)

{

if (request.Method == HttpMethod.Post && request.Headers.Contains(_header))

{

var method = request.Headers.GetValues(_header).FirstOrDefault();

if (_methods.Contains(method, StringComparer.InvariantCultureIgnoreCase))

{

request.Method = new HttpMethod(method);

}

}

return base.SendAsync(request, cancellationToken);

}

}

Notice the code to return base.SendAsync as the last line of the method.

In other cases, a message handler might only want to change the response and not touch the request. An example might be a message handler to add a custom header into the response message (again a sample from the ASP.NET site). Regardless of which framework version is in use, the code will need to wait for base.SendAsync to create the response. With the C# 4 compiler, a friendly way to do this is using a task's ContinueWith method to create a continuation.

protected override Task<HttpResponseMessage> SendAsync(

HttpRequestMessage request, CancellationToken cancellationToken)

{

return base.SendAsync(request, cancellationToken).ContinueWith(

(task) =>

{

var response = task.Result;

response.Headers.Add("X-Custom-Header", "This is my custom header.");

return response;

}

);

}

With C# 5.0, the async and await magic removes the need for ContinueWith:

async protected override Task<HttpResponseMessage> SendAsync(

HttpRequestMessage request, CancellationToken cancellationToken)

{

var response = await base.SendAsync(request, cancellationToken);

response.Headers.Add("X-Custom-Header", "This is my custom header.");

return response;

}

Another set of handlers will want to short-circuit the pipeline processing and send an immediate response. These types of handlers are generally validating an incoming message and returning an error if something is wrong (like checking for the presence of API required header or authorization token). There is no need to call into base.SendAsync, instead the handler will create a response and not allow the rest of the pipeline to execute. For example, a message handler to require an encrypted connection:

protected override Task<HttpResponseMessage> SendAsync(

HttpRequestMessage request,

CancellationToken cancellationToken)

{

if (!Uri.UriSchemeHttps.Equals(

request.RequestUri.Scheme,

StringComparison.OrdinalIgnoreCase))

{

var error = new HttpError("SSL required");

var response = request.CreateErrorResponse(HttpStatusCode.Forbidden, error);

var tsc = new TaskCompletionSource<HttpResponseMessage>();

tsc.SetResult(response);

return tsc.Task;

}

return base.SendAsync(request, cancellationToken);

}

There is still a call to base.SendAsync for the case when the request is encrypted, but over a regular connection the code returns an error response using a TaskCompletionSource. I think of TaskCompletionSource as an adapter for Task, since I can take code that doesn't require asynch execution (or is based on asynch events, like a timer), and make the code appear task oriented.

In .NET 4.5, Task.FromResult can accomplish the same goal with less code:

var error = new HttpError("SSL required");

var response = request.CreateErrorResponse(HttpStatusCode.Forbidden, error);

return Task.FromResult(response);

This concludes another electrifying post on the ASP.NET WebAPI.

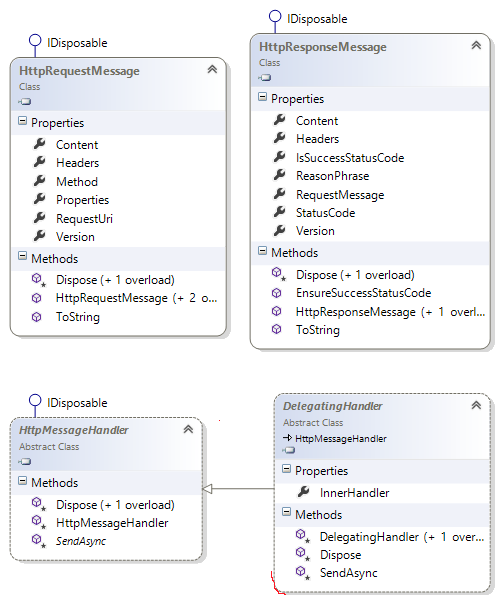

The WebAPI framework is full of abstractions. There are controllers, filter providers, model validators, and many other components that form the plumbing of the framework. However, there are only three simple abstractions you need to know on a daily basis to build reasonable software with the framework.

- HttpRequestMessage

- HttpResponseMessage

- HttpMessageHandler

The names are self explanatory. I was tempted to say HttpRequestMessage represents an incoming HTTP message, but saying so would mislead someone into thinking the WebAPI is all about server-side programming. I think of HttpRequestMessage as an incoming message on the server, but the HttpClient uses all the same abstractions, and when writing a client the request message is an outgoing message. There is a symmetric beauty in how these 3 core abstractions work on both the server and the client.

There are 4 abstractions in the above class diagram because while an HttpMessageHandler takes an HTTP request and returns an HTTP response, it doesn't know how to work in a pipeline. Multiple handlers can form a pipeline, or a chain of responsibility, which is useful for processing a network request. When you host the WebAPI in IIS with ASP.NET, you'll have a pipeline in IIS feeding requests to a pipeline in ASP.NET, which in turn gives control to a WebAPI pipeline. It's pipelines all the way down (to the final handler and back). It's the WebAPI pipeline that ultimately calls an ApiController in a project. You might never need to write a custom message handler, but if you want to work in the pipeline to inspect requests, check cookies, enforce SSL connections, modify headers, or log responses, then those types of scenarios are great for message handlers.

The 4th abstraction, DelegatingHandler, is a message handler that already knows how to work in a pipeline, thanks to an intelligent base class and an InnerHandler property. The code in a DelegatingHandler derived class doesn't need to do anything special to work in a pipeline except call the base class implementation of the SendAsync method. Here is where things can get slightly confusing because of the name (SendAsync), and the traditional notion of a pipeline. First, let's take a look at a simple message handler built on top of DelegatingHandler (it doesn't do anything useful, except to demonstrate later points):

public class DateObsessedHandler : DelegatingHandler

{

protected async override Task<HttpResponseMessage> SendAsync(

HttpRequestMessage request,

CancellationToken cancellationToken)

{

var requestDate = request.Headers.Date;

// do something with the date ...

var response = await base.SendAsync(request, cancellationToken);

var responseDate = response.Headers.Date;

// do something with the date ...

return response;

}

}

First, there is nothing pipeline specific in the code except for deriving from the DelegatingHandler base class and calling base.SendAsync (in other words, you never have to worry about using InnerHandler).

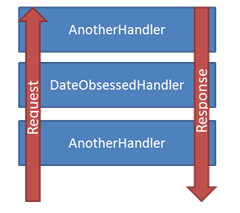

Secondly, we tend to think of a message pipeline as unidirectional. A message arrives at one end of the pipeline and passes through various components until it reaches a terminal handler. The pipeline for WebAPI message handlers is is bidirectional. Request messages arrive and pass through the pipeline until some handler generates a response, at which point the response message flows back out of the pipeline.

The purpose of SendAsync then, isn't just about sending. The purpose is to take a request message, and send a response message.

All the code in the method before the call to base.SendAsync is code to process the request message. You can check for required cookies, enforce an SSL connection, or change properties of the request for handlers further down the pipeline (like changing the HTTP method when a particular HTTP header is present).

When the call to base.SendAsync happens, the message continues to flow through the pipeline until a handler generates a response, and the response comes back in the other direction. Symmetry.

All the code in the method after the call to base.SendAsync is code to process the response message. You can add additional headers to the response, change the status code, and perform other post processing activities.

Most message handlers will probably only inspect the request or the response, not both. My sample code wanted to show both to show the two part nature of SendAsync. Once I started thinking of SendAsync as being divided into two parts, and how the messages flow up and down the pipeline, working with the WebAPI became easier. In a future post we'll look at a more realistic message handler that can inspect the request and short circuit the response.

Finally, it's easy to add a DelegatingHandler into the global message pipeline (this is for server code hosted in ASP.NET):

GlobalConfiguration.Configuration

.MessageHandlers

.Add(new DateObsessedHandler());

But remember, you can also use the same message handlers on the client with HttpClient and a client pipeline, which is a another reason the WebAPI is symmetrically beautiful.

A one and a half minute teaser for my upcoming Pluralsight course:

Happy April 1st ...

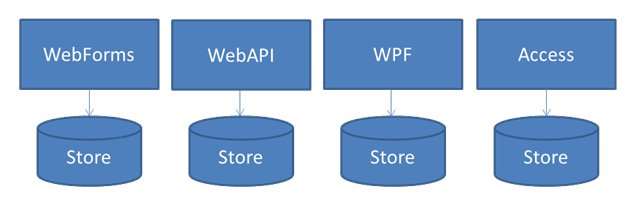

It doesn't take long to realize that the HTTP methods POST, GET, PUT, and DELETE can map directly to the database operations we call CRUD (create, read, update, and delete).

It also doesn't take much effort to find samples that demonstrate CRUD applications with the WebAPI. In fact, the built-in scaffolding can give you code where the only software between an incoming HTTP message and the database is the EntityFramework.

Is CRUD all the WebAPI is good for? That's a question I've heard asked a few times.

I think one of the reasons we see CRUD with the WebAPI is because CRUD is simple. CRUD is the easiest approach to building a running application. CRUD is also the easiest approach to building a demo, and for explaining how a new technology works. CRUD isn't specific to the WebAPI, you can build CRUD applications on any framework that sits on the top or the outer layer of an application.

All the above applications would have these characteristics:

- Minimal business logic

- Database structure mimicked in the output (on the screen, or in request and response messages).

There is nothing inherently wrong with CRUD, and for some applications it's all that is needed.

Let's not talk about WebAPI as yet, let's talk about these 2 WPF scenarios:

1) When the user clicks the Save button, take the information in the "New Customer" form, check for required fields, and save the data in the Customers table.

versus

2) When the user clicks the Save button, take the information from the "New Customer" form. Send the data to the Customer service for validation, identification, and eventual storage. If the first stage validation succeeds, send a message to the legacy Sales service so it has the chance to build alerts based on the customer profile. Finally, send a message to the Tenant Provisioning service to start reserving hardware resources for the customer and retrieve a token for future progress checks on the provisioning of the service.

#1 is simple CRUD and relatively trivial to build with most frameworks. In fact, scaffolding and code generation might get you 90% of the way there.

#2 presents a few more challenges, but it's no more challenging with WPF than it would be with the WebAPI (in fact, I think it might be a bit simpler in a stateless environment like a web service). The framework presents no inherent obstacles to building a feature rich application in a complex domain.

Of course, you should think about the problem differently with the WebAPI (see How To GET A Cup Of Coffee, for example), but most of the hard work, as always, is building a domain and architecture with just the right amount of flexibility to solve the business problem for today and tomorrow. That's something no reusable framework gives you out of the box.

OdeToCode by K. Scott Allen

OdeToCode by K. Scott Allen