Looking back over the history of the Entity Framework provides some interesting lessons.

Microsoft released the first version of the Entity Framework in August of 2008. One month later, the investment bank of Lehman Brothers filed the largest bankruptcy case in the history of the United States, and thus began the worst global economic downturn since the great depression.

Coincidence?

Probably.

Although the Entity Framework first appeared in 2008, the story begins much earlier. Microsoft has a long history of inventing and re-inventing data-oriented developer tools and frameworks. Applications like FoxPro and Access are long-standing examples, while Visual Studio LightSwitch is a modern specimen. FoxPro and Access were both successful products, and LightSwitch, while still new, shares the same practical attitude to working with data. All these products allow you to build a data centric application with little architectural fuss.

For .NET developers working in C# and Visual Basic, there were several times when we thought we would also see a focused, practical, no-nonsense approach to working with data. While the .NET framework has always provided abstractions like the DataSet and DataTable, these abstractions essentially represented in-memory databases complete with rows, relationships, and views. However, since C# and Visual Basic are both object-oriented programming languages, it would seem natural to take data from a database and place the data into strongly-typed objects with both properties (state) and methods (behavior). One solution we thought was coming from Microsoft was a framework named ObjectSpaces.

ObjectSpaces was described as an object/relational mapping framework, and like all ORM frameworks ObjectSpaces focused on two goals. Goal #1 was to take data retrieved from SQL Server and map the data into objects. Goal #2 was to track changes on objects in memory so when the application asked to save all the changes, the framework could take data from the objects and insert, update, or delete data in the database. In “A First Look at ObjectSpaces in Visual Studio 2005”, Dino Esposito used the above diagram to illustrate these capabilities.

Unfortunately, ObjectSpaces never saw the light of day.

In the spring of 2004, Microsoft announced a delay for ObjectSpaces in order to roll the technology into a larger framework named WinFS. WinFS was one of the original pillars of Longhorn (the now infamous codename for Window Vista), and WinFS promised a much larger feature set compared to ObjectSpaces.

The idea behind WinFS was to provide an abstraction over all sorts of data – relational data, structured data, and semi-structured data. WinFS would allow you to search data inside of Microsoft Money just as easily as tables in SQL Server, calendars in Exchange Server or images on the file system, as well as provide notification, synchronization, and access control services for all data sources, everywhere.

Although some of these ideas had been around since the early 1990s (the Object File System of Microsoft’s Cairo operating system), WinFS was hoping to deliver the vision and offer a quantum leap forward in the way you develop with information.

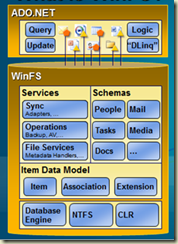

At the 2005 Professional Developers Conference, Microsoft used the following diagram in WinFS talks. When compared to the previous ObjectSpaces diagram, this diagram is more theoretical and focuses on concepts (Schemas and Services) instead of actions (moving objects from SQL Server and back).

Despite all the talks about quantum leaps in working with data, Microsoft decided it would not ship WinFS as part of Windows Vista, and on June 23, 2006, Microsoft announced that WinFS would not be delivered as a product. Perhaps this was due to the overly ambitious goals of being all things to anything data related, or perhaps it was due to a heavy focus on architectural issues and not enough focus on the practical and mundane. Matt Warren provides an insider’s view in his post “The Origin of LINQ to SQL”.

We on the outside used to refer to WinFS as the black hole, forever growing, sucking up all available resources, letting nothing escape and in the end producing nothing except possibly a gateway to an alternate reality.

From the outside it looks like WinFS was a classic case of taking a specific problem (I need to access a data) and over-generalizing to the point where the original problem gets lost in the solution. Joel Spolsky wrote about this problem in a post entitled “Don’t Let Architecture Astronauts Scare You”.

The Architecture Astronauts will say things like: "Can you imagine a program like Napster where you can download anything, not just songs?" Then they'll build applications like Groove that they think are more general than Napster, but which seem to have neglected that wee little feature that lets you type the name of a song and then listen to it -- the feature we wanted in the first place. Talk about missing the point. If Napster wasn't peer-to-peer but it did let you type the name of a song and then listen to it, it would have been just as popular.

In retrospect, this was a dark time for Microsoft systems and frameworks. Windows Vista delayed shipping until 2007. WPF (aka Avalon) is today not capable of writing genuine Windows 8 applications. WCF (aka Indigo) is under pressure from lightweight frameworks that embrace HTTP, like the ASP.NET Web API. Windows Workflow was subsequently rewritten from scratch after its initial release, and Windows CardSpace is now defunct.

ObjectSpaces failed because it was hauled into a larger vision that was excessively ambitious and over generalized. We’ve seen over the years that the best frameworks start by solving a specific problem, solving it well, and then evolving into something bigger (the shining example being Ruby on Rails). The spirit of agile and lean software development has taught us to continuously deliver something of value, and apply YAGNI ruthlessly. Iteration and shipping bits were not a priority for the WinFS project.

However, you can’t fault Microsoft for thinking big and trying to innovate. Innovation often involves stepping away, trying something different, trying something big, and sometimes failing. Failure, and learning from failure, can lead to new directions and better inventions.

When Microsoft announced the end of WinFS as a product, it also promised to deliver some of the features and ideas encompassed in WinFS through new and different products. One of these products would be the Entity Framework. Would the Entity Framework learn from past mistakes? We’ll take a look in the next post.

OdeToCode by K. Scott Allen

OdeToCode by K. Scott Allen